Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude

I first discovered Stacia Spragg-Braude’s work back in 2000 or 2001 when she was just Stacia Spragg, no Braude, and working at the Albuquerque Tribune in New Mexico. I had just graduated from the University of Missouri and was starting my first job as a newspaper photojournalist at the Naples Daily News in southwest Florida. I don’t remember where exactly I saw her work, maybe in a newspaper, a magazine or maybe in the Pictures of the Year contest, but I saw enough of it here and there over the years for it to make an impression.

Years later, 2007 I believe, putting in some time as an editor at Blueeyes Magazine, the brainchild of friend and inspirator John Loomis, I had the privilege of working with Stacia and editing a version of her long-term project on the Begay’s, a Navajo family living on their reservation in Arizona, for the magazine.

Looking through Stacia’s initial submission and then later through a larger selection of her photographs, I remember being struck by the beauty, power, mystery and intimacy of the black and white images of a landscape, culture and people I was unfamiliar with. I recall feeling that she’s not only a fiercely dedicated and determined photojournalist, but must have an intense personal connection and relationship with this family to spend roughly a decade making these photographs and telling this family’s story.

Now, two years after working with her for that issue of Blueeyes, I discovered, through one of the weekly Photo-Eye “New Arrivals” email newsletters I receive, that Stacia’s “To Walk in Beauty: A Navajo Family’s Journey Home” has been published and is on sale (here and here and here) . I immediately sent her an email to congratulate her on the book, her success and good fortune and asked her if she would be OK with me posting a little something on my blog.

Below is a Q&A we had via email. Enjoy.

MATTHEW: Tell me about yourself and how you got started with photography and why you chose the photojournalism/documentary path with your work?

STACIA SPRAGG-BRAUDE: I guess I’ve always had a camera with me, though growing up it was a disk camera (remember those, with really tiny negatives on a wheel that looks like a ViewMaster card)? I studied journalism as an undergraduate, but switched over in grad school to cultural geography. It was actually my Russian studies geography professor who told me I was in the wrong line of business when I tried to convince him to let me photograph my Master’s thesis on ethnic Turks in Bulgaria instead of compiling endless research and writing about them. That and I can’t read a map. So I switched to studying photojournalism at the University of Missouri in the early 1990s. In terms of deciding to specialize in photojournalism, to me that was what photography intuitively was. It wasn’t a conscious decision to specialize since that’s what I had been doing all along without having a name for it.

M: With the newspaper/magazine/media business being what it is, and with a lot of photographers losing their jobs either by taking buyouts, getting laid-off or deciding to leave by their own accord, I’m curious about your time at the newspaper and why you left?

SSB: I only had one internship with a newspaper while studying at Missouri, and that was with the Albuquerque Tribune. Right after that, I joined their staff and I spent about 8 or 9 years working with them. It was a fantastic place for photojournalists, since we had a great deal of autonomy, and creativity was encouraged and expected. There really wasn’t even a box to try to think out of, you know? I decided to leave in 2005 when I realized I had used up all my vacation and comp time and couldn’t take my honeymoon. That and I was really burned out…kept looking at the clock wondering when I could finish my assignments and go rock climbing instead. I had no idea what I would do next, but I knew then I needed to take a leap of faith (or stupidity) and find “next.”

M: Has it worked out the way you thought it would? Any regrets?

SSB: No, it hasn’t worked out the way I thought it would. And yes, it has worked out the way I thought it would. I left in 2005 when the photojournalism world was still fantastically different from now and I envisioned doing projects abroad and actually getting paid for it. But I got pregnant right away and basically spent the next 10 months eating Krispy Kremes and wondering how the hell I would salvage my professional life, or if I was doomed to trading a camera bag for a diaper bag. When Junior came, it wasn’t quite as dire as my imagination lead me to fear and I got inspired to turn the Navajo project into a book, because I felt I had come full-circle in the bigger picture of life, and more importantly, the Begay family I had photographed had come full circle as well. It was time. I stopped worrying about following a certain path that I had laid out in my mind and in so many dreams as we’re encouraged to do, and instead found the beauty in making things up as I went along, and accepting burn-out as a necessary weigh-station for the soul to find its next adventure. In other words, I followed the advice of my friend and fellow photographer, Scott Lewis, and stopped trying to force things like creativity, inspiration, project ideas, etc., and let things just come to me. It’s much harder than it sounds at first, but then it’s incredibly easy, like eating pancakes.

M: How did your long-term project on the Navajo family, the Begay’s begin? How many years have you been working on it? Is it complete or is this the kind of story you will keep coming back to?

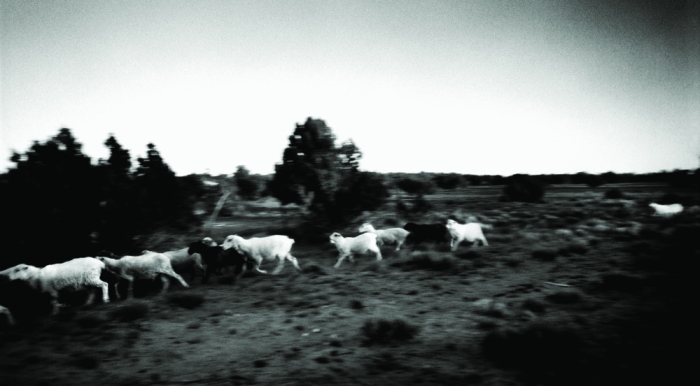

SSB: I met the Begays rather by chance during my internship at the Tribune back in 1996. We became friends, and I spent weekends here and there with them, going to different Navajo ceremonies, herding sheep, eating lots of frybread and hanging out. As a photographer/story-teller, I was fascinated and inspired by how they were committed to passing down a legacy to their children, and how they were intent on saving their culture and identity. They lived several hours away, and most family members didn’t have phones then. So I’d get out as often as I could, and I missed a lot of stuff, to be sure.

When my internship ended, I didn’t want to leave New Mexico because I was captured by this project, so I took a job tutoring English that paid crap but gave loads of un-paid leave so I could spend chunks of time driving to the reservation. After being hired full-time at the Tribune in 2000, I continued working on the project, though not as frequently because of other assignments. I made it out there for special ceremonies, events, etc., and kept everything on my own time so I retained the copyright. Over the years the Tribune did publish some mini-stories, such as when Heather had her coming-of-age ceremony, and the editing/scanning and that sort of thing were done on company time since that particular article was for the paper. But otherwise I kept it separate (thank God I had enough sense for that…) This all unfolded over the course of 10 years.

The story is definitely not complete (is it ever?), but I felt in 2006 that the timing was right for a book when Makiyah was born. She was the fourth generation of the family that I had photographed. I had started photographing her mother, Heather, when she was maybe 10, and now she was having a child of her own, and wanting to have the same traditional ceremonies for her daughter. The journey I had witnessed with this family had come full-circle in my mind, and as I mentioned so had I when my son was born, and my inner voice told me it was time. I had to let go of it then, and with it, a piece of my life. All of my 30’s was connected to photographing this family.

M: You said all of your 30’s were connected to this family and telling their story. How did this project and the Begay family influence your own life?

SSB: Wow, now that’s a question. Hmmm, I don’t think I’m that much different from other photographers, perhaps photojournalists specifically, whose lives become so interwoven and twined together with the communities and individuals they are shooting that it starts to define them. I think that’s the great beauty of being a photographer, that you can enter into these other worlds and realities, spend some time there, and return to your own, but by doing so you have expanded your place on the earth, and you are never the same. In other words, there’s no boundary between your work and who you are; photography is not a job, it’s just how you pass through life. It’s not just the images that define you, or the portfolio, but it’s all those people and places and things that you experienced as a photographer who make you who you are. They will always be with you. To me that’s a great comfort. It’s kind of like a violin in the way the wood, and consequently the sound it makes, starts physically changing and forming in its own unique way over time based on who is playing it. So the past is always very much alive inside you. It creates your sound.

For me, I spent a lot of time traveling and shooting in my 20’s, and getting my heart broke, having many adventures, but always looking for a sense of home. While spending time with and photographing the Begay’s in my 30’s, I saw a family in their imperfect but beautiful and determined way trying to hold on and define who they were as a people and family and where they came from. In other words, their identity. And while photographing that, unbeknownst to me, I was forming my own identity and putting together all the things I had learned in life from my elders and my experiences. So actually most of the images in the book turn out to be very auto-biographical. It’s always a waltz between the photographer’s soul and that of the person or place they are photographing.

M: Can you talk about the process of working on a long-term project like this? I know it takes a lot of time, patience and determination to stick with it and not abandon it half-way through and move on to the next story. What drove you to keep going back and spending time with this particular family?

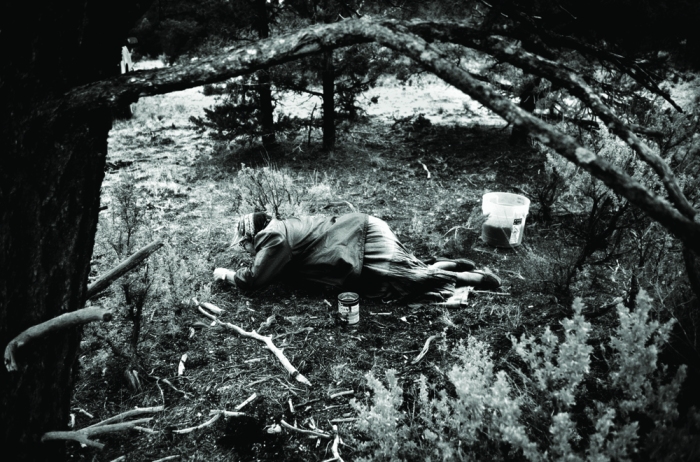

SSB: Oddly, I don’t consider myself a long-term project photographer. That just sort of happened with this project because it was a good counter-balance creatively to working for a newspaper. I had no expectations on the project (well, maybe a few), no editors, no deadline, no rules. So why quit? Besides, we were and continue to be friends, and part of each others’ lives, so all the time spent out there wasn’t just “work.” That being said, there were several times I felt like I was creatively burned out and not producing any meaningful pictures. When it started feeling like I was forcing myself to make pictures and to see, I backed off and said it was time to let go. At one point I spent 6 weeks living in a hogan with the family. It sounds dreamy for a photographer, and there were moments and time in there that were ethereal and magical. But many other days too when I was feeling creatively bored, seeing the same thing over and over, eating too many carbs, and feeling sleepy. I didn’t look at those negatives for at least a year afterwards, but eventually found that many of the images had incredible meaning and symbolism years later, but not then. Funny how that works. Don’t trash your negatives (or digital files).

M: Do you still keep in touch with them?

SSB: Yes, we are still friends. In fact, a couple of the family members married my husband Darren and me. But I no longer really photograph them. I just let go of that, at least for now.

M: As you’ve already mentioned, this same story is also the subject of your new book “To Walk in Beauty: A Navajo Family’s Journey Home.” Can you talk about how getting this project published came about and talk about your experience and the process? How much control did you have and did you ever consider self-publishing?

SSB: I had no idea what I was doing when I first sought a book publisher. I attended Review Santa Fe and met with a few book editors there, which was a big help in terms of really understanding what they’re looking for in a photo book proposal. I had advice that covered the spectrum, from showing a complete mock-up (whether an artist’s hand-done, one-of-a-kind book or an In-Design produced rough draft) of how I envisioned the book, to the more minimalist approach of just showing book publishers the photographs to see if they would be interested. I ended up designing a signature, which for me consisted of 6 or 7 pages I designed with the text and photographs in In-Design, printed on nice paper with my Epson printer and then simple-stitched together by a local book-binder. I sent the signature along with the book proposal, each publisher has a different proposal to fill out (you can usually find these on the publisher’s websites). Since it was time-consuming to do these proposals, I carefully made a hierarchy of publishers I would contact. I started with 4 or 5 university presses in the Southwest, since it was important for me to find a publisher that had a background and understanding of the Navajo culture.

I also really wanted to find a publisher that would be willing to allow me as the photographer to be involved in the whole process of editing, designing and proofing. After that initial round, I had plans to contact publishers who specialized in photo books like Nazraeli, Phaidon, etc., but I never made it to that round since the Museum of New Mexico Press contacted me and was interested in offering a contract. I felt like it would be a good match for this book.

Three publishers right off the bat were interested. So I had to figure out what my priorities were. For me, I wanted to avoid having to put up any of my own money or take the time to find grant money to fund the publishing. I’ve heard this is pretty common for photographers trying to publish photo books. Secondly, I wanted to have some involvement in the editing and design stages. And thirdly, I hoped to get the book published in a timely fashion, so it wouldn’t languish on some shelf and grow old. I knew going into this that I wouldn’t make any money off a photo book, so I didn’t have that expectation. The Museum of New Mexico Press had the money to publish the book, and had a small staff that I had a good feeling about. And they wanted to release it in a year, which is a relatively fast turn-around in the book world. I hired a photo consultant (Joanna Hurley) to look over the contract the Press was offering and make suggestions before I signed it.

Over the next several months, I worked with an editor at the Press on the written part of the book. The designer, David Skolkin, who just recently helped found Radius Books, liked my design approach and went with it, adding and modifying with his improvements and style. I did all the scanning and toning myself (the project was shot on film), despite reading advice to hire out for this and call in the professionals. I’m sure that would have been nice, but I didn’t have the money to do that, and I felt like well, the conditions weren’t perfect when I shot it, half the damn time I was shooting with expired film pushed too much, so why not just use my crappy scanner and see what happens. It will be good enough. And I’m happy with the end result, but it took a few aneurisms and melt-downs during the proof stages to get there (for the first proofing, the printer thought I really didn’t want the shadows so dark and decided to just… open them up! I really did have heart palpitations.

Another confounding aspect was when the designer instructed me to choose a duotone color. I felt like I was painting the Queen’s bathroom or something, with too many swatches in Photoshop spread out over the floor. I furiously made too many prints covering the whole damn color spectrum, and it all changed depending on my mood, what kind of light you were viewing them in, etc. Ultimately the designer and I came across a black and white photo book which had a duotone we loved and felt wonderful for my work. We sent that book to the printer (in Singapore) and asked them to match it. And no, I wasn’t on press when they printed it, though everyone will tell you to try and be there. It just wasn’t realistic for me since they didn’t have an exact run date, and the last-minute tix from here to there were like $3000. Wasn’t going to happen. I like to buy shoes and film and wine too much. So I burned effigies and wore the same socks and muttered spells under my breath the whole time they were printing in hopes that it would translate into a good press run with happy pressmen. It worked. The book looks better than I ever imagined.

One more note regarding control in the process. While the designer liked my approach and didn’t muck with the edit I presented them, and I felt that the book staff listened to my input and respected my opinions, ultimately He Who Pays For the Press Run, Owns the Press Run. So if the publisher put up the money, they have final say-so over everything. They also asked for my “thoughts” on the cover’s image, and I offered 3 or 4 photo “suggestions.” But it’s clear that the publishers do the final selection. Which I think is okay since they really wanna sell the damn book. But I think this is why self-publishing is a better route for some folks, and I would have considered that if I had not found a publisher whom I felt I could work with.

M: What was the experience like? Is there anything you would do different?

SSB: The experience was a bit nerve-racking since I had no idea what to expect. I was used to working with newspaper and magazine editors. After making the signatures, I muddled my way through the minimum one needs to know to create a document in In-Design and made a mock-up of the book so I could show publishers how I envisioned the book feeling, but also to help me with the photo editing and flow. I would definitely encourage photographers interested in doing a book to consider this step, intimidating as it may seem. I’m a minimalist (or maybe just lazy and hate using a computer), but you can’t just show a stack of photographs that have consumed you in the making and expect designers and editors to intuitively know exactly how you want a book to feel. I am definitely not a designer, but I definitely knew how I wanted the flow to go, the tone of the book, how it should feel in the readers’ hands. The more articulately you can discuss and present this, the better. Perhaps the publishers might have a better idea for the design, and hopefully you can arrive at that together, but at least they know where you are coming from up front. That’s just my opinion, but then again maybe I just have a control issue with a project that was a dominant force in my life for so many years.

M: How did you decide on the final edit of the book? Did you work with any editors or others to help finalize what was published.

SSB: I went back through the 6 or 7 binders full of negatives and did a very wide edit, maybe of at least three times the number of photos I thought I’d finally end up with. Hell, just about anything that was in focus I circled in red wax pencil. I made plain paper print-outs, rented a cabin in the mountains for a couple of days, and whiddled that down to 80 or 100 photographs. I didn’t just select the pictures that I felt were the best either, I also included pictures that I was irrationally attached to, and other images that went along well with the oral histories I excerpted throughout the book. The flow of the photographs had to be inter-woven with the flow of the stories the family was telling in the text, so it follows a story line, much like a long epic poem. It’s not chronological or subject-related. My friend and fellow photographer, Scott Lewis, helped at this point to make sure what I wanted to say as a photographer would make any sense to readers. That input is vital.

The next and final phase came after drinking much wine one night and realizing that the body of work paralleled a Navajo prayer which illustrates in words how the Navajos traditionally approach life. In the Navajo’s world, “beauty” embodies being centered, balanced, to have peace with yourself and with others around you, to walk this path of beauty. I structured the flow of photographs to follow the words of this prayer: to walk in beauty with beauty behind me (the world of the ancestors and the old ways), with beauty around me (traditions being passed to the younger generations), with beauty above me (the realities of 21st century life on the reservation and the death of the elders), and ending the book with beauty before me (the birth of the next generation).

M: What kind of advice can you pass along to other photographers who want to publish a book?

SSB: Besides the things I mentioned above, here are some other suggestions. The first and foremost I actually heard from Darius Himes, a founder of Radius Books who at the time was with Photo-Eye. He said to absolutely know why you are doing a book. It seems a simple question, one that is obvious, but I think it can be highly nuanced and will give you direction if you answer it honestly. For me, it was the chance to weave together my images with the Navajos’ words to create a narrative poem of their journey as I saw it. I liked the idea of putting that poem down permanently in a book, which has a very different feel than in other media such as the internet, magazines, newspapers, museum exhibits. And that mission statement dictated how I edited.

For instance, it wasn’t about necessarily assembling my best portfolio work to showcase, it wasn’t about trying to use the book as a springboard for getting future assignments or projects, it wasn’t about making money, it wasn’t about making a photo album for the family, it wasn’t about trying to impress editors or win awards. I think all of those motivations for doing a book are fine, as long as photographers are honest with themselves up front, because that is going to dictate the edit, who you decide to go with to publish it, whether you publish it yourself, whether you are willing and able to put up money to get it published, whether it’s paperback or hardcover, etc.

After that, look at photo books you like and who published them. See what other titles those publishers have released, and whether your work would be a good fit for them. Do as much research as you can to see if there are other photo books similar to the one you are proposing, and determine how yours will be different, better, complementary to the body of work already out there. In other words, you’re going to have to convince the publisher that your book is needed and desired. Really try to figure out your audience, that will not only help with your editing, but you need to know how and to whom you are going to market it, and you’ll have to provide fairly specific suggestions to the publisher.

Besides other photographers, who would want to buy your book? Are there specific organizations, clubs, schools, etc. that would be interested? Try to get as specific as you can. And find someone who knows your work whom you respect who can help you edit. I had the misconception that the publisher would want to sit down and edit the work with me. That wasn’t the case for me, though I’m sure every publisher is different. Mine just wanted the completed work. But regardless of that, before you approach any publisher, you should have a pretty clear idea of the edit you like, and work it out from there. There are so many more things I could suggest, but I guess this is a start!

M: I find it very interesting that you have been working as a farmer for the last coupe of years. How did this come about and how does it fit in with your photographic career? Do you see any similarities between working the land and growing food and being a photographer? Now that the book is published, what’s next? Are you working on a new project?

SSB: How the hell I got into farming. I live in the village of Corrales, along the Rio Grande, here in New Mexico. It’s one of the oldest continually farmed areas in the country, being farmed by Native Americans for centuries, then by the Spaniards after their arrival in the 1600s. I’ve been active for years with a group that tries to help preserve farmland by helping landowners put some of their land in a trust so that they retain ownership but that limits develop. A couple of years back, when I was really burned out on photography, another committee member said “Hey, let’s farm” and I couldn’t think of any reason not to. Some folks with land by the river allowed us to use their land (they can get a tax benefit) so we just planted a lot of things on a little over an acre, and somehow started specializing in various types of potatoes, white ones, blue ones, red ones, yellow ones. It’s sort of random, but not really, because it’s just another way of being connected into life’s deeper cycles and in the community, something that I feel photography has given me, especially at the newspaper. I love being covered in dirt, I love the hot sun on me, I love not being attached to a computer, I love feeling like I’m doing something real. And quite often in photography, I felt limited, like I wasn’t really doing something real, just photographing others doing something real. And I love doing something so intimate and vital, like growing food.

That being said, I’ve discovered I’m at heart a story-teller, and this year I’m helping an 80-year-old farmer with her farm and fruit orchard here in Corrales while I do a book about her. I’m just following the muses on this one, I’m definitely not driving, but playing around with writing more and shooting with an old Brownie 8mm movie camera. I hope to start writing a collection of essays with some images of her this winter, once the harvest is all done.

[…] Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude « Eat The Darkness eatthedarkness.wordpress.com/2009/10/26/interview-with-stacia-spragg-braude – view page – cached + One Bachelor, Five Friends, a Boat, the Ocean, Cold Beer, Six Dolphin Fish and One Hammerhead Shark. Good Times — From the page […]

Twitter Trackbacks for Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude « Eat The Darkness [eatthedarkness.wordpress.com] on Topsy.com

October 26, 2009 at 3:28 AM

Thank you for sharing this energizing and life inspiring interview. This morning i was blue and now i feel a little boost that will help me go on with the day.

I also find it very true that if one stops trying to force things like creativity, inspiration, project ideas, etc., and let things just come to them it creates a natural flow that will lead the person into their unique journey, guided by their emotions and feelings. Creatively it also can help you free yourself from outside influences and esthetic trends.

romain

October 27, 2009 at 9:24 AM

[…] You find the original post here eatthedarkness.wordp … | eatthedarkness […]

City Guide Naples - Tips for Overnight Accommodation, Leisure and the latest News from Naples

October 29, 2009 at 7:29 PM

[…] There’s a good interview with photographer and farmer Stacia Spragg-Braude at Matthew Ratajczak’s blog, “Eat The Darkness.” […]

Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude at “Eat The Darkness” » NOTEBOOK

October 30, 2009 at 12:48 AM

[…] Excerpt from: Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude « Eat The Darkness […]

Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude « Eat The Darkness

November 9, 2009 at 3:07 PM

[…] There’s an interview with photographer and farmer Stacia Spragg-Braude at Matthew Ratajczak’s blog, Eat The Darkness. […]

APhotoADay Blog » Blog Archive » Interview with Stacia Spragg-Braude

November 15, 2009 at 10:08 PM

[…] a decade making these photographs and telling this family’s story.” There is a wonderful interview with my dear friend and former colleague at The Albuquerque Tribune Stacia Spragg-Braude that I […]

Interview with New Mexico photographer Stacia Spragg-Braude | Steven St. John Blog

November 16, 2009 at 2:39 PM

beautiful, just beautiful

Kenneth Dickerman

December 10, 2009 at 4:14 PM